Normal and Abnormal Mood States

Euthymia

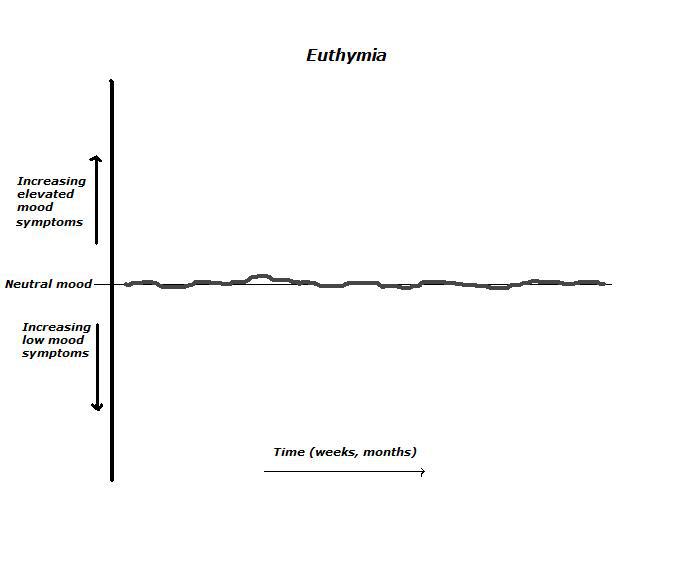

Euthymia describes a normal mood or emotional state. Our moods are normally tied appropriately to life events and developments. A job promotion, for example, may lead to a “good mood” of happiness and pride in our work, which is entirely appropriate. Also appropriate to that event may be some measure of anxiety, associated , for example, with the prospect of meeting increased job demands or responsibilities. In either case, the resulting emotional changes should be neither extreme nor very long lasting. We may “ride a high” to some degree for a few days or so, but typically things balance out and a more neutral mood ensues. And even when we’re feeling good about ourselves as a result of the promotion, we don’t normally take the occasion to develop an extreme sense of self-importance or grandiosity, become overactive or overtalkative, or engage in productive or pleasurable activity to such a degree that it assumes more importance to us than getting adequate sleep.

If that promotion produces anxiety, or if some other life event about which we are sad or anxious occurs, we don’t typically become so distressed that we develop hopelessness or suicidal thoughts, severe anxiety and self-loathing, sleeplessness, or appetite declines with significant weight loss. Our “negative” emotions are normally not extreme enough to affect our functioning in any way, and are normally not long-lived. We “bounce back” in a few days or weeks. We might represent such a normal mood state over time with an irregular wavy line, each point on which represents our average mood state in response to life events at a given moment in time:

The affective domain of our experience is the feeling, as opposed to the thinking, part of our minds. The affective realm involves emotions, moods, and drives.

Emotions are brief or fleeting feeling states that typically change over seconds or minutes—such as anger when another driver cuts us off, or pleasure at experiencing something humorous. Moods are longer-lasting feeling states that color our experience, and typically change over hours or days or weeks. If we are having a “bad day”, we may evaluate or experience the same event more negatively than we would on a good day. Such a low mood may make similar events more likely to “bring us down” when mood is low. Drives are normally persistent and relatively unchanging affective elements that greatly influence our behavior, such as hunger for food, sexual urges, and sleep.

Mood disorders involve more than just disturbances in mood, and are thus often called affective disorders. Signs and symptoms include not only disturbances of mood, but of the entire affective domain, including emotions and drives as well. One useful way to think about people suffering from affective disorders is that their emotions/moods/drives are prone to become disconnected from, or are no longer normally tied to, life events. Someone suffering from classical, severe depression, for example, continues to feel downhearted regardless of life events, and may be unable to experience pleasure or happiness even with the most positive developments.

Affective disorders typically are associated with episodes of abnormally low or elevated mood states, in which emotional state is no longer normally responsive to life events, and drives become disturbed. In an episode of mood disorder, the severity of the symptoms fluctuates over time, and in some sufferers may resolve completely, possibly even without treatment. Treatment reduces the severity, duration and frequency of episodes but, especially without treatment, affective disorders tend to be recurrent, episodic conditions–not unlike an asthma sufferer who is prone to episodes of difficulty breathing. Between episodes, people with mood disorders may have no symptoms whatsoever, their moods again become normally tied to life events, and drives return to normal patterns, as in non-affected individuals.